More-than-human thinking: moth

Fluttering your thinking into moth-like thought

I’ve been unsure how to begin writing about more-than-human thinking. I have taught myself many things, privately, but to openly reach for thinking differently? Writing about thinking seems difficult and self-indulgent.

I took heart over the weekend after reading an interview in Imagine5, Amitav Ghosh wants to give nature its voice back. Ghosh, a spectacular writer, is calling for people to become more comfortable with more-than-human thinking, and he questions:

“The fundamental problem is that language and speech are human attributes, as we understand them … So how do we find a way of giving a voice to non-human entities?”

That’s the way I’m looking for. It’s not that I am uncomfortable in this practice of imagining other, more-than-human perspectives. The harder part is trying to step into the collective, to make it visible. At the risk of never starting, I’m going to just try.

How this will work

At the start of the month, a post like this, posing relational questions for thinking.

At the end of the month, a post where I try to write from a non-human perspective.

I will hone this way as I go along, over time. My goal is to make it easier for you to join in if you want to. I’m still finding my way.

September is moths.

Moth events

First, I conjure the interaction I remember with moths in my life. (What are yours?)

The terror of the giant moth invasion

A gathering of giant brown moths - an eclipse or whisper in language - that would gather in my hometown, silently emerging from vast kilometres of salt-bush landscape in remote South Australia. I am playing in the street under the last sky-dregs of red autumn sunset, a scent of rain in the evening. The sky fills with hundreds of these giant brown rain moths — bigger than my eight-year-old hand (up to 17 cm long) — dinner plate-wingspan — they could have covered my whole face. As parents switched porch lights on, I joined other shrieking children to run inside. It was as if they chased us indoors, flapping at the screen door to hasten us to dinner and bed. So, fear is my first memory of moths.

Being imprinted by moth dust

Around the same age, a wayward moth flew into my face in daylight, as I rode my bike down the street. It slapped me in the forehead. I went home, crying, feeling disgusted when I looked in the mirror to find a weird dusty moth-print on my forehead. It felt branded, marked. I could still feel its imprint long after I washed my face. I have a memory of overreacting because my brother remembers my trauma from this event, too. I felt quite haunted by that bodily moth experience for reasons I can’t articulate. Something close to horror.

A Suburban Moth

My fear of moths stayed with me. In my teens, searching for bad metaphors, I wrote a poem called Suburban Moth that has many questionable moth references, like “the moth and I composing our own elegies, as the shadows bleed towards us”. Yikes. Teenage angst about “life and its nothingness” apparently was more moth than goth for me. So, moths were deeply seated within, as harbingers of gloom.

Encountering a bird-moth

And then the wonder, the enchantment came. My encounter with a Hummingbird Hawkmoth in the first garden that was ever my own in my early 20s. In my ecological confusion about whether I was looking at a bird or a moth, somehow, there began a shift in my understanding of moths. I became curious then, and in love with them. I will now usually photograph them out of fascination. It’s even ok if one slams into my face while I am wearing a headtorch.

Moth patterns

So the pattern of my moth encounters began in fear and disgust, seismically shifting into wonder in some unintended transition based on my experiences. The patterns of my mind changed.

The nights are getting warmer into Spring where I am, so while I have seen moths in the headlights as I drive along dirt roads, I have yet to notice any around my house. I have always associated moths as creatures of warm nights, but I have learned that moths are not that simple. To be a moth is a spectrum.

We like to say:

”drawn like a moth to a flame” a lot.

That idea is everywhere.

Moths in the pages of poetry and plays

When I think about moths in literature and poems, I think of transformation, fear, omens, and shadowy death mongers. Ideas that I feel came after my own fears, and validated them. What comes to mind as I started to think about this over the weekend, with certain writers already fluttering around me, are the moth that '“Haunts Candles” in Emily Dickinson’s ‘A Moth the hue of this’, Blake’s spiritual warning '“Kill not the Moth nor Butterfly/For the Last Judgement draweth nigh’. Then, Yeats’ ‘moth-like stars flickering out’ from The Song of Wandering Aengus is always in my head when I point my telescope to the sky, as well as the in-betweenness of “The moth-hour of eve” from The Ballad of Father Gilligan.

There is also the idea of moth-as-faery/fairy. For example, the mischievous fairies Cobweb, Mustardseed, Peaseblossom and Moth, who are minor characters in my favourite Shakespeare play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In the many performances of the play I have seen, Moth the fairy brings some memorable mothly-fairy stage presence. When Blake illustrated A Midsummer Night’s Dream, he painted brown literal wings on Moth, but there is speculation/evidence that Moth is a misnomer, for ‘mote’ as in tiny. The fairy moth may have never been.

Anyway, I am sure you will have your own literary, art, music or film moths that flutter around in your thinking.

Moth systems

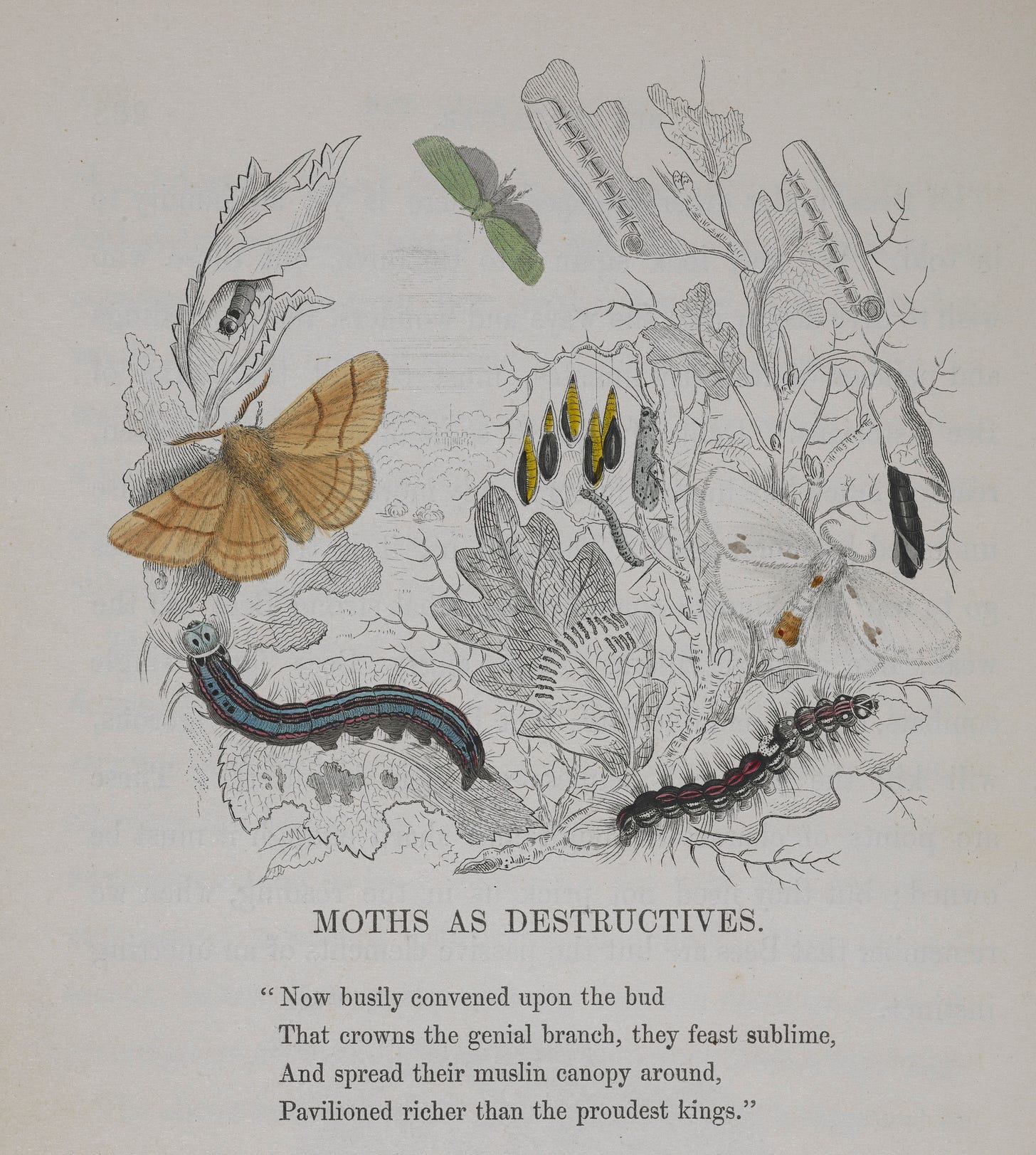

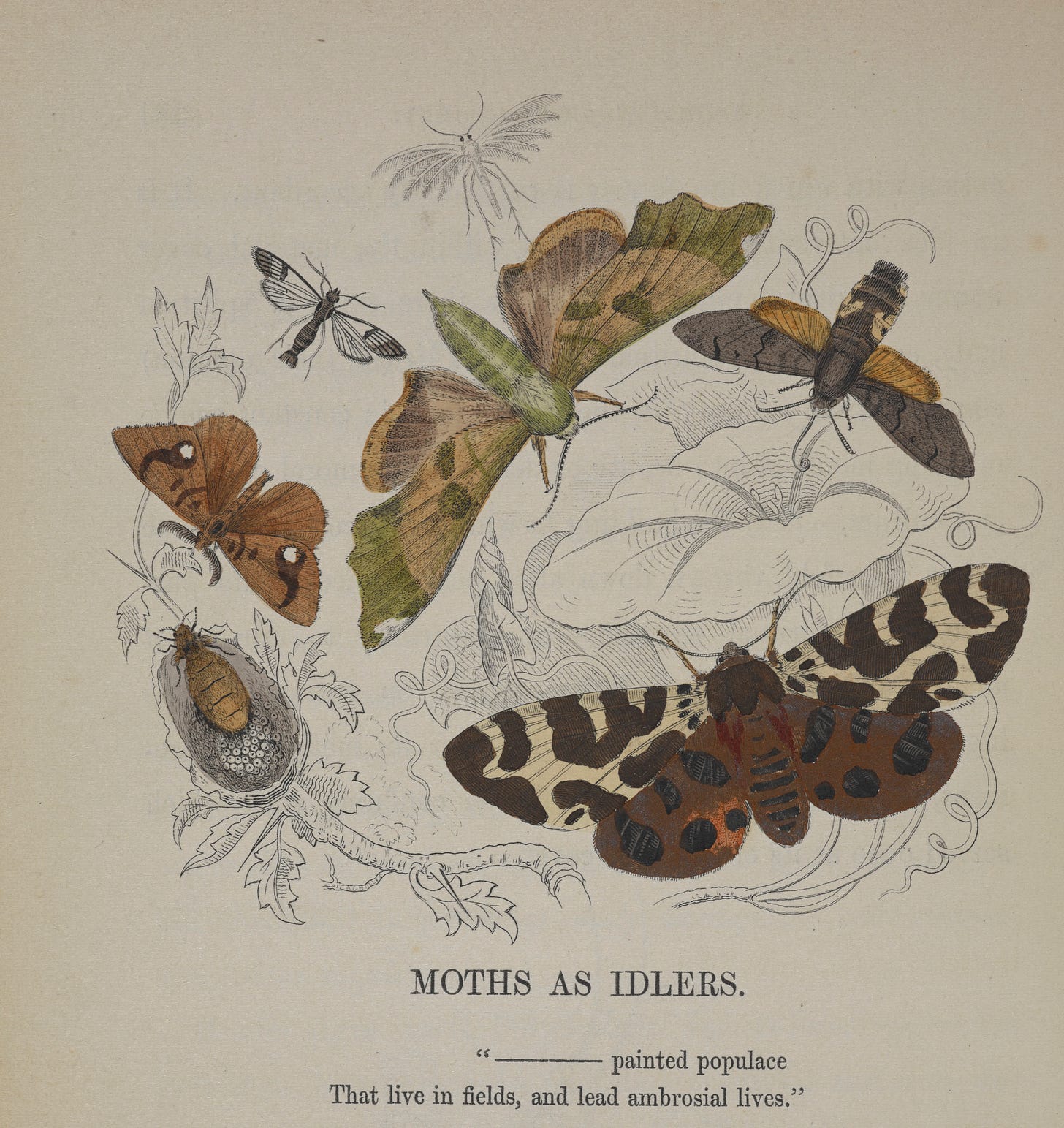

We tend to know moths in their binary relationships as not-butterflies, but ‘other’. They are more nocturnal than butterflies, but there are night moths and day moths and in-betweeners (nocturnal, diurnal, crepuscular). They are not always muted in colour, often labelled “brown and dull”, and many have evolved as bright and vivid as butterflies. They can be hard to tell apart. Moths often rest with their wings spread horizontally, but they can also rest with their wings folded vertically, like a butterfly, too. Their eyes gather so much more light than butterflies, but they have poorer vision.

One of the latest understandings of how moth navigation systems work shows how deeply our assumptions are held. It’s a popular and beautifully romantic idea that they navigate celestially, compulsively drawn to the light of the moon. The cool, dark new romantics of the insect world. However, the latest research suggests that moths actually tilt their back to the light to spatially orient themselves, and this light source to tilt in relation to, would have originally been the moon. Not so now. With so much artificial light, moths are spatially “trapped in the glow”, tilted, flipping and utterly disoriented in space.

Moth mental models

Dominant:

moths are just night-flying butterflies

moths are a symbol of attraction and fragility, loners dumbly drawn to their own doom by the compelling lure of light

moths are pests, devourers of food and clothing; they must be prevented!

Alternative:

moths are diverse and have their own evolutionary adaptations and niches

moths are complex beings, sometimes even social, doomed because of artificial light that creates an ecological trap

moths are important pollinators, have a relationship with night-blooming plants, bats, birds and countless other species

Moth power

What power do moths have in our human-created systems? One of the biggest power imbalances is the control humans now exert over darkness, with artificial light.

If you have ever experienced vestibular dysfunction, this is quite a relatable hell to exist in, impacting moths and other species. Hence, the rising advocacy for Dark Sky and limiting artificial light at night. Having lights that point down and have shrouds/shields and minimising blue and UV lighting are the key actions we can enact in our human spaces.

If moths have any power in our light-dominated world, it seems beyond visible and hidden power; it’s invisible. They can’t turn our lights off.

Moth thinking practice

So what does this all mean for shifting from thinking about moths to thinking like a moth?

Here are four relational questions that I am going to think about for the rest of September, while I observe and encounter moths in my daily life.

How do particular events (emergence, appearance, being drawn to light) reshape my encounters with moths and the meaning I give to their presence?

What recurring pattern in moth behaviour (nocturnal flight, attraction to flame or light, or migration/gathering) feel like a metaphor for my human experience?

How do moths interact with the ecological systems I am aware of (biodiversity, pollination, nocturnal/crepuscular/diurnal prey), and how can I express my understanding of these systems?

How do human systems and assumptions (light, farming, bias towards the beauty of butterflies) shape which moths survive and which are found in the human cultural imagination?

These are the questions I’ll start with, moving into new questions that shift my thinking into the perspective of a moth, as hard as that will be.

By the end of the month, I hope I can write a few paragraphs from a moth perspective that feels learned.

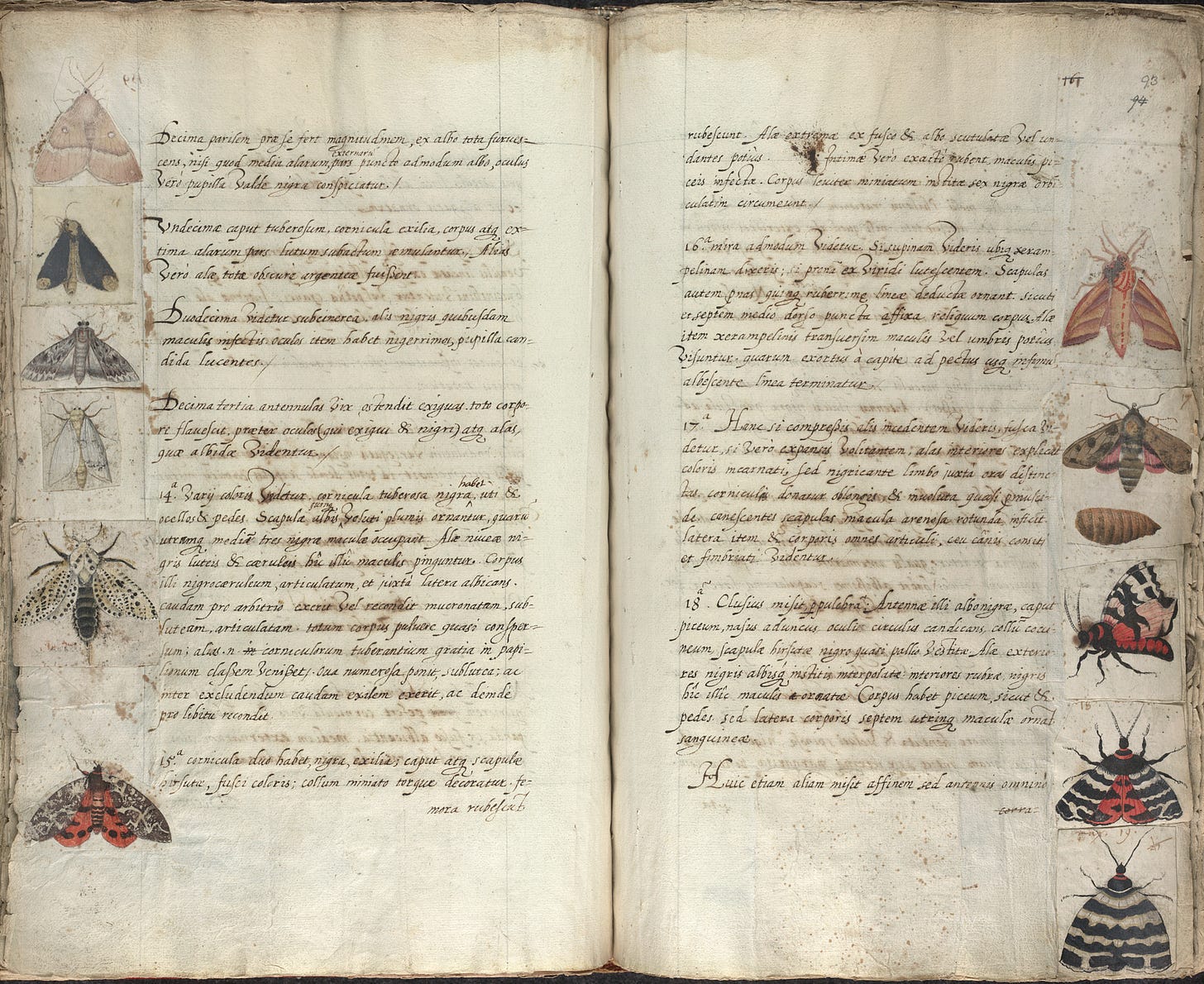

Images used in this post

The public domain moth images are from Episodes of Insect Life by Acheta Domestica, pseud. L.M. Budgen, London, 1849-1851, used courtesy of The British Library archives. You can also browse and search the full text of this remarkable book online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library.